Kimono-the happiness of the ladies

Wednesday March 8, 2017: Kimono-the happiness of the ladies at MNAA Guimet, visit conference by Sylvie Ahmadian, Specialist lecturer in Asian art, attached to the Guimet museum.

The collection presented comes from the venerable women's fashion house, Matsuzakaya, founded in 1611 in Nagoya, at the beginning of the Edo period (1603-1868). This collection, begun in 1931, presents a panorama of the Japanese feminine fashion, it is for the first time exposed outside Japan.

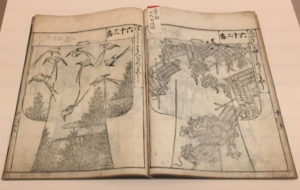

In 1745, a Matsuzakaya branch was established in Ueno, in Edo (present-day Tokyo). Catalogs of models were published by the Matsuzakaya house and 180 editions were published in two centuries, the first going back to 1666. We see the back kimonos with different patterns; customers would choose a model and a store salesperson would show them a life-size pattern with all the details. These catalogs have sometimes changed fashion and women bought them like we buy a women's magazine today.

Angyusai Enshi. Interior view of the Ueno shop (Matsuzakaya House). 1772. Polychrome printing nishiki-e. Detail of a polyptych. |

Example of a catalog in three volumes published by the House Matsuzakaya in 1704. |

The Edo period saw Japan withdraw into itself and keep only sporadic relations with China, Korea and the Dutch East India Company. This involves, for artists, a return to traditions and the Japanese will develop in all fields an artistic production of great originality and extraordinary richness. The political and social system instituted by the Shogunate obliges the nobles to have a residence in Edo and divides the society into three classes: the warriors (buke) (shogun, imperial family, samurai and nobles), peasants and, in the lower strata of society, artisans and traders (chonin). As a result of the enrichment of these, the economic power will move, and many merchants will be richer than many nobles. As they were not allowed to own homes in the country or palaces in town, these merchants will spend their money in entertainment and that's when the neighborhoods of pleasure appear, including the famous Yoshiwara in Edo (Tokyo).

When the capital was moved to Edo in 1603, it became the economic and artistic center of Japan. There are all craft activities and weaving workshops have also been created, but the most luxurious textile weaving center remains Kyoto, the imperial capital.

It is not known exactly when the kimono was introduced in Japan but it is attested in its form kosode at the time Heïan (794-1185) and, at the time Kamakura (1185-1333), it is the clothing worn daily by the warrior class. From the time of Edo, merchants and bourgeois will also adopt the kosode made of silk. It's at 18rd s. that the term kimono (from kiru et mono, literally "thing that one wears on oneself) seems to have been used to designate a type of garment in general, but the terms of kosode andOsode are always used: the kosode designates a garment with "short sleeves" and tubular whose opening was just large enough for the passage of the hand and the arm, theOsode having long sleeves with wide openings. The kosode does not take into account anatomical differences between men and women and requires a fairly strict maintenance, especially that the bust is maintained by a wide belt, theobi, which is Corsican. The kosode is made up of 7 textile strips making 35cm wide which are assembled in the same way for centuries. The evolution of kosode will assert itself, not in its form that remains virtually unchanged, but in its decor.

A painting by Moronobu Ishikawa (1618-1694) of a "beautiful standing woman" illustrates the fact that one could wear several kosode Bunk.

Un kosode the 18rd s. in silk crepe, has a typically Japanese decor of paper walls and larches that combines geometric patterns with naturalistic motifs.

Moronobu Hishikawa. "Beautiful woman standing". Colors on paper. Late 18th century. |

Kosode with larch motifs and paper sides. Stained tincture on silk crepe. Beginning 18e s. |

Kosode with undulating lines and chrysanthemums. Silk brocade karaori. Detail. 2e half of 16e s. © Sylvie Ahmadian. |

Un kosode the 16rd s. patterned wavy lines and chrysanthemums was made in a silk brocade karaori (Weaving method in which the raw silk warp threads and the worked silk thread give the impression of an embroidery) particularly sumptuous.

The fabrics used can be simply dyed, embroidered, with patterns dyed in reserve (yuzen zome) such kosode with white water and iris patterns: the patterns are first drawn in reserve with the technique of bosen (glue is applied to repel the dye) then dyed indigo color. The fabric is then steamed to fix the dye and remove the glue. The iris and white water motifs were then delicately embroidered. For some luxurious fabrics, the glue of the patterns is applied with a brush, which allows very sophisticated landscape compositions. Another technique, the shibori zomeis to ligate or sew some parts of the fabric, to coat them with glue to make them impervious before dipping the fabric into the dye. Finally, the technique of the stencil, katagami, allows to obtain areas or patterns in reserve that can optionally be painted later. Sometimes, three techniques can be used in the decor of a kimono in addition to embroidery.

Un kosode in white satin adorned with embroidered chrysanthemums is typical of the 17ème s fashion. with an ornamentation that starts from the left shoulder to finish towards the hem of the right side, drawing an arc in a very dynamic composition.

Kosode with chrysanthemum motifs. Kanoko shibori tincture and embroidery on white silk satin. 2e half of 17e s. © MNAAGuimet |

Katabira with camellias, cherry blossoms and bats. Reserve dyeing, embroidery and coating of gold threads on blue linen. Late 18th century. - early 19th c. |

Uchikake patterned successive quarter circles and young pines. Reserve tincture on damask silk. 1e half of 19e s. |

Au 18rd s., women of the warrior class buke will favor damask silks or silk crepes embellished with embroidery, sometimes the shibori zome is also used.

THEuchikake is an outer garment, ample and heavy, it is worn without a belt.

The katabira are kosode informal houses, particularly during the summer months. They are unlined and usually made of linen. A sumptuous example of 18rd s, in blue linen, is enhanced with camellias and cherry blossoms and bats on the shoulders. The dye is made to reserve and the motifs are in embroidery and bend of gold threads.

Le furisode is a kosode with long sleeves, especially worn by young girls. An example in embroidered yellow silk, from the beginning of 19rd s., presents a decor illustrating the feast of red and yellow leaves of autumn. It is with extreme finesse that the motifs, first in reserve, then embroidered, start from the hem down the back to go up to the collar on the front. They evoke themes drawn from the Said of Genji. Theatrical or literary-inspired motifs abound in the decorations of the kimonos, showing that the owner is a cultivated woman.

Furisode with autumn yellow and red leaves festival illustration. Detail. Yuzen tincture and embroidery on a yellow silk background. Beginning 19e s. |

Wedding keychain in maki-e lacquer and accessories. Beginning 19e s. |

Uchikake with holster pattern containing shells to play. Kanoko shibori tincture and embroidery on a damask silk background. Beginning 19e s. |

The marriage of a girl allows to deploy an extraordinary luxury in the trousseaux. These wedding trousseaux could include between 300 and 500 lacquered pieces, often in lacquer Maki-e decorated with gold or silver. All these objects were not always intended for daily use and they constituted a heritage and were passed from one generation to the next, as a family treasure. A wedding trousseau of the daughter of a feudal lord from the beginning of the 19rd s. shows the diversity and richness of the furniture and accessories, all adorned with peonies, coats of arms (ka-my) of the Takatsukasa family, and of diamond motifs in Maki-e on black background. Shelves with trunk supported the necessary incense, toilet and make-up supplies, office supplies and writing desk. At the time of her marriage, the girl must have several uchikake that she changed during the day.

Un uchikake sumptuous wedding dress, in white damask silk, is embroidered with patterns of cases containing shells to play (kai-awase). This game, very popular with women, allowed to highlight its literary and pictorial culture.

Pair of pins with pendants, decorated with peonies and hydrangeas. Beginning 19e s. |

Obi with oxen carts, bamboo and mauves. Embroidery on silk crepe. Beginning 19e s. |

Kosode with representation of the Grand Sumiyoshi Shrine. Yuzen dye and embroidery on a damask silk background. Middle 18e s. |

Kosode with orchids in the snow and calligraphy. Yuzen dye, nori bosen dye and embroidery on indigo silk crepe. 2e half of 18e s. |

Like the kosodeHairstyles have also evolved over the centuries. While in Heïan times, the hair was very long, down to the ground and just tightened by a link in the back, the ways of arranging the hair over the shoulders grew much at the time of Edo, may be at the instigation of courtesans. To keep these buns very complex, leaving the bare neck (the most sensual and erotic part of the human body for the Japanese), we used all kinds of combs and pins. Decorative combs could be made of lacquered wood, ivory or tortoiseshell. The pins were usually made of metal and adorned with different plant or animal motifs and some had pendants that moved when the woman walked or shook her head.

An essential element of the Japanese costume is theobi, large belt that allowed to keep the crossed of the kimono closed. Worn by men and women, theobi However, it is much longer and more richly decorated for the latter. An example in purple silk crepe is embellished with rich embroidery of bamboo, mauve and ox carts, while another, in white satin, is embroidered with light patterns of pines, bamboo and plum.

From the 18rd s, fashion will favor calligraphy patterns and landscapes. A kosode 18rd s. is adorned with embroidered landscapes of remarkable delicacy similar to painting. It refers to the Sumiyoshi Grand Shrine in Osaka Prefecture. A kosode crepe de Chine from the same period presents a pattern of orchids covered with snow and calligraphic characters of a poem waka from Said of Genji.

From the Meiji era (1868-1912), Japan enters the modern world and the upper class will abandon the wearing of kimono in favor of Western clothing. The other social classes will continue to wear the traditional costume but we see an evolution in dyes that become synthetic, allowing a greater variety of colors than natural pigments. A hitoe intense purple, patterned with cherry and peony, dyed to spare, is a good example of the production of the end of the 19rd s.

Hitoe patterned cherry and peonies. Stained tincture on silk crepe. End 19e s. |

"Casanova" coat with wide kimono sleeves by Callot Sœurs. Crepe de chine, lamé yarn. 1925. |

Coat-mandarin, quilted silk, printed linden and glycine green and purple. Yves Saint Laurent. 1994. |

Kimono "Oiran". Silk and polyester. Junko Koshino. 2009 |

The discovery of Japan by Westerners at Universal Expositions will lead to a Japanese fashion in all artistic fields. The dresses will take the form of kimonos and especially we will use Japanese silk. The fashion designers of the beginning of 20rd s. will be inspired by the forms and decorations of this Japanese exoticism. A “Casanova” coat by the Callot sisters takes up the wide kimono sleeves and the richness of the decor is reminiscent of Japanese court clothing. Paul Poiret will also sacrifice Japanese fashion by creating a wrap dress in silk crepe, crossed on the front, with long sleeves and an asymmetrical decoration.

After the Japanese fashion of the end of 19rd s. and the beginning of 20rd Japan is not going to be fashionable any more and it will be necessary to wait for the 1960 years, period when Japanese creators will arrive in Paris, to see again the fashion to be inspired and to reinterpret the kimono. Kenzo, then Issey Miyake will draw their inspiration from the Japanese cultural heritage and breathe new Japan into fashion. Yves Saint Laurent, Jean-Paul Gaultier and John Galliano will thus be inspired by kimono shapes as well as Japanese fabrics and decorations.

Contemporary Japanese designer Junko Koshino strives to respect the soul of the kimono and the spirit of Japan while creating easy to wear clothes. For the kimono Oiran (name given to the courtesans of the Edo period), it takes the exaggerations of the fashion of the time by modernizing them. It also uses all the resources of traditional weaves such as gold thread embroidery, sheet metal applications or inserts of gold paper strips.